On Jails

The Mass Incarceration Problem in America

This article originally appeared in Vice : By Grace Wyler

July 2014

The United States has an enormous prison problem. A more-than-2.4-million-prisoner-sized problem, to be precise, locked up in the archipelago of federal penitentiaries, state corrections facilities, and local jailhouses that form the nation's thriving prison-industrial complex. Since 1980, the number of incarcerated citizens in the US has more than quadrupled, an unprecedented rise that can attributed to four decades of tough-on-crime one-up-manship, and a draconian war on drugs.

Today, more than one out of every 100 Americans is behind bars, and the US has the largest prison population in the world, both in terms of the actual number of inmates and as a percentage of the total population. The numbers are staggering: the US incarceration rate is nearly 3.5 times higher than that of Mexico, a country that has spent the last decade in the throes of an actual drug war, and between five and ten times higher than those seen in Western Europe. There are more people locked up in the US than in China. In fact, the US is home to nearly a quarter of the world's prisoners, despite accounting for just 5 percent of the overall global population.

But the data gets even more disturbing when broken down at the state level. A recent analysis by the Prison Policy Initiative shows that while states like Louisiana have undoubtedly led America's march toward mass incarceration, no state or region has been immune to the prison boom. And each state is a global aberration, with incarceration rates that compare to those found in isolated dictatorships and countries recovering from civil war.

As the chart shows, 36 states have higher incarceration rates than Cuba, the country with the world's second highest prison rate. New York comes in just above Rwanda, which is still trying thousands of people in connection to the 1994 genocide. Even Vermont, birthplace of Phish, Ben & Jerry's, and the country's only socialist senator, imprisons a higher percentage of its population than countries like Israel, Mexico, or Saudi Arabia.

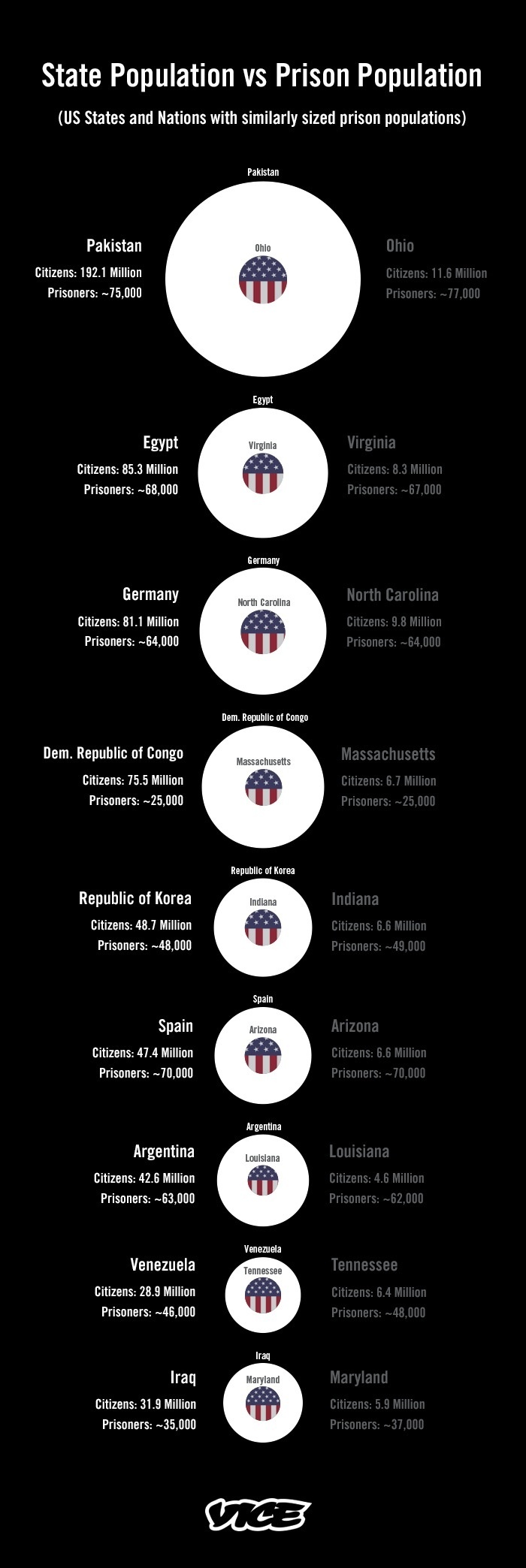

Looked at in terms of actual inmate numbers, this means that the number of people behind bars in most US states is on par with the prison populations of entire nations. And not Luxembourg or Burundi. Big, messy countries, like Venezuela and Egypt.

“The question here is are we using prison too much, and when you compare one US state to another US state, you start to think ‘Eh, maybe it’s all just the same,’” said PPI Executive Director Peter Wagner, who co-authored the analysis. “But the bigger picture here is that every single state is out of step with the rest of the world.”

“Other than the United States, most of the countries with high incarceration rates have had a very recent social trauma," Wagner added. “New York has the same incarceration rate as Rwanda and there has not been a massive genocide in New York State. The irony is that New York actually used to have a much higher rate of incarceration. It's actually one of the grand exceptions in the country, of a state that has been reducing its prison population."

The numbers, Wagner explained, underscore the central role that states have played in America’s unprecedented prison buildup. While much of the recent prison debate has centered on federal sentencing laws and drug policy reform, the real mass incarceration action has taken place at the state level. According to PPI data, more than half of US inmates — 57 percent — are in state prisons, and another 30 percent are incarcerated in local jails, generally for violating state laws. Though prison rates have varied widely across the US, all 50 states have implemented some set of policies — like mandatory minimums, “truth in sentencing” policies, or “three strikes” rules — aimed at putting more people in prison for longer periods of time.

Unsurprisingly, the economic and social impacts of this trend have been massive. According to a 464-page report published by the National Research Council earlier this year, state spending on corrections increased 400 percent between 1980 and 2009. The result, the NRC points out, is that prisons are now some of the primary providers of health care, counseling, and job training to the country's most disadvantaged groups. Meanwhile, the social and cultural costs of mass incarceration are disproportionately borne by poor communities, minorities, and people with mental illnesses.

And the actual benefits of mass incarceration are minimal, at best. Sure, crime rates have gone down since 1980, but studies have found the connection between increased prison rates and lower crime is tenuous and small. In fact a report released by The Sentencing Project this week found that in states that have substantially reduced their prison population in recent years, like California, New York, and New Jersey, the crime rate has actually fallen faster than the national average.

“It's really a situation of diminishing returns for public safety,” said executive director Marc Mauer. “And the amount of crime control that we produce becomes less over time as well.”

Recently, though, there are signs that America is doing a rethink on its experiment with mass imprisonment. Earlier this month, the US Sentencing Commission voted to retroactively extend lighter sentencing guidelines to about 46,000 prisoners currently serving time for federal drug crimes, a move that was endorsed by the Department of Justice. Efforts to implement criminal justice and federal sentencing reforms that would have been unthinkable just a few years ago have been gaining traction from both parties in Congress, forming a rare left-right coalition that is decidedly soft on crime.

At the state level, tight budgets have forced governors and lawmakers to ease drug lawsand relax harsh incarceration policies, and to look for more cost-effective criminal justice solutions, including investing in better drug treatment and parole programs. Even in Louisiana, the world’s prison capital, Republican Governor Bobby Jindal has passed modest measures, setting up an early release program for some nonviolent drug offenders, although he recently vetoed stronger sentencing reforms.

“We’re always going to have prisons and we're always going to have crime, but many states are starting to rethink their drug policies, their sentencing laws,” said Mauer. “The impact is not dramatic yet, but I think there's no question that the climate is beginning to shift. The question is how far can we go now that we’ve started to move in the other direction.”